Influence of Autism Diagnosis on Anorexia Nervosa Pathology and Prognosis

This blog is derived from and in reference to the Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy Bulletin.

My Story: Development Through the Lifespan

I was a happy child, with many saying I was quirky, in my own world, but appeared content to be there. However, as I got older, I noticed increasing turbulence in how I was feeling, becoming far more aware of feeling different. It felt like everyone around me got a book of how to behave in social situations, what to say, how to act, how to dress…and I did not get a copy. Autistic women often report a vulnerability when it comes to social interactions, leading to burnout from difficulties navigating such situations. Brede et al. (2020) reported that autistic women experiencing eating disorders described long-term struggles pertaining to navigating social settings and expectations contributing to poor mental health. This study additionally found that all 44 autistic women participants reported having long-term struggles as it pertains to navigating social settings and expectations.

I wanted to fit in and to be accepted, so I copied those around me in a desperate attempt to fit in, be accepted, and get it right. I do not think I ever achieved this and I really started to struggle. Social rejection is a risk factor for depression for individuals with autism, as is camouflaging, more commonly known as masking (Cage et al., 2018). According to the National Autistic Society (n.d.), masking is commonly (consciously or unconsciously) used by autistic people to appear neurotypical.

As I got older, these difficulties—or differences—grew more noticeable and my mental health began to decline. I was constantly anxious, especially in social situations, and felt exhausted from trying to uphold a mask and be the person I thought I needed to be. This is not uncommon for autistic people with studies indicating prevalence rates of children who are autistic and experience a comorbid anxiety disorder anywhere between 11-84% (White et al., 2009). As soon as I was alone and the mask would drop, I experienced intense overwhelm and would shut down, worsening my self-esteem and self-concept, and making me feel even worse about myself.

Social Impacts of Neurodivergence

The pressure of school became unmanageable and my perfectionistic tendencies spun out of control. While perfectionism and obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD) are not mutually exclusive, they do have overlapping qualities, similarly to how OCD symptoms can overlap with qualities and features of autism (Postorion et al., 2017). I struggled to make or keep any friends, struggled to relate to anyone around me and whilst I desperately tried to keep up with what was trendy, fashionable, and what I felt I should be interested in, I wasn’t. This aligns with the overarching reported experience with being autistic, highlighting the impact of feeling like you’re “failing” in society, and that your differences may even be your fault (Brede et al., 2020).

I became a target for bullies because I was easy. I didn’t react to their attacks; just lowered my head and willed myself to be invisible. I stopped speaking, hid away, and wanted to disappear. No matter how hard I tried, I felt broken and fundamentally flawed as a person. Feeling a lack in a sense of self and identity is often a catalyst for autistic individuals to begin copying or mirroring those around them to fit in. Autistic individuals may also make their body, their nutritional intake, and/or their dynamic with food as impressive or as perfect as possible in an effort to counteract the feelings of not fitting in or being good enough for the neurotypical society (Brede et al., 2020). I had become so shut down, internalized, and unreachable. My mental health hit rock bottom when I became utterly convinced that I was not fit to live in this world anymore. Autistic individuals are more prone to bullying with factors such as geographic location and school setting shown to impact the frequency and severity of bullying incidents. Occurrence rates of various types of bullying are estimated to be around 10% for physical bullying, 45% for verbal bullying, and 15% for relational bullying (Maïano et al., 2016).

Progression: Eating Disorder Diagnosis

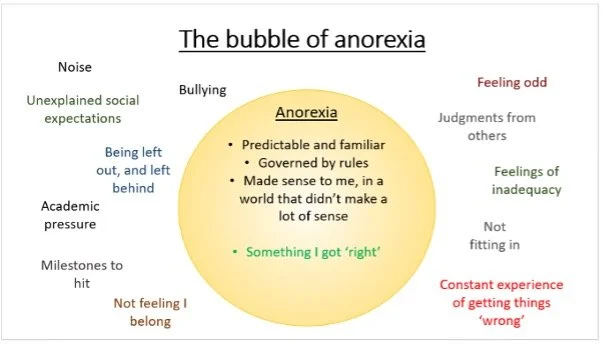

Anorexia came into my life rapidly and aggressively. Autistic individuals may be highly susceptible to the egosyntonic nature of the pathology of anorexia nervosa due to their receptiveness to the functional components of eating disorders that combat longstanding psychological distress (Gregersten et al., 2017). I quickly spiraled from a normal relationship with food to needing crisis intervention. The anorexia felt like I had finally found a way to cope. The image below is a self-created depiction of how anorexia felt for me (Hollings, 2025).

It felt like a bubble.

On the outside were all the things I did not feel able to manage: the loudness, brightness and vividness of life, the building academic and social pressures I did not feel capable of keeping up with, not fitting in, not feeling I belonged. Most of all, however, was the chronic feeling of getting things wrong and subsequently being wrong as a person. This experience highlights why autistic individuals tend to seek out or respond to the mechanism of escaping negative emotions. As the experience is so dire, relief from the experience feels imperative (Gregersten et al., 2017).

The bubble that anorexia provided was a stark opposite of the outside world. Instead of multiple layers of chaos, noise and confusion, there was just one commanding voice— anorexia. The bubble was predictable and routine, governed by rules and providing a sense of structure. It felt simpler: anorexia commanded something, I obeyed, and anorexia was happy. And that felt like I could finally do something right. Studies show that autistic individuals are seeking a reclamation of control, structure, and guidelines in their life, all of which the anorexia nervosa portrays to provide (Gregersten et al., 2017). Unfortunately, these functions of the disorder do not last. The bubble wasn’t safe for long and it quickly became suffocating. I was trapped, though at the time it felt like a safe haven.

It was never about weight, weight loss, or body image for me. Losing weight felt like a side effect to behaviors I felt compelled to do as part of my routine or rituals. When I first entered treatment, they spoke about body dysmorphia and body positivity at a healthy weight. This was something I did not experience, leading me to feel like I was also getting treatment wrong, further perpetuating the feelings of wrongness. This is in alignment with other autistic individuals’ experiences who feel the uniqueness of their co-occurring presentation with autism spectrum disorder and anorexia nervosa is not being tailored to by standard eating disorder treatment (Kinnaird et al., 2019).

Through a biopsychosocial lens, there may also be a biological component to the likelihood of these two disorders with oxytocin being a mediating factor. Research indicates that when looking at autistic groups, there is a high ratio between oxytocin synthesis to the nonapeptide oxytocin, showing the overall imbalance of this system. When looking at the cerebrospinal fluid of women with anorexia, oxytocin is much lower than it is for individuals with bulimia and for individuals in the control group (Odent, 2010).

Progression: Autism Diagnosis

During my adolescence, I endured many hospital admissions due to my mental health with lengthy stays, robust medication regimens, invasive interventions, and an overall traumatizing treatment experience, especially for an undiagnosed autistic person. With early diagnosis of autism influencing positive overall mental health outcomes, the lack of diagnosis at this age may have significantly impacted the efficacy and prognosis of treatment methods at this time (Brown et al., 2024).

Through it all, I continued to learn; I learned what helped me and what did not help me. I learned what to do and what not to do when I struggled. I didn’t know it then, but most of these were adaptations for autism. Autism had been mentioned a couple of times, but I had quickly dismissed it based on the narrow stereotype I had of autism. There is an array of perspectives and reactions associated with diagnosing autism spectrum disorder, with one study showing that 40% of diagnosed individuals feeling dissatisfied with this diagnosis at the time (Crane, 2018).

In the meantime, I finally managed to get home and even started university. On the surface, I looked better. But the feeling of being broken and inherently flawed remained. During this time, the thought of being autistic grew and I finally did my research. I read books and blog posts, learning about the spectrum, and it finally felt like something made sense. I spoke to my psychiatrist about it and we agreed. An accurate diagnosis and thorough assessment of clinical presentation allow for tailored interventions to meet functional needs, influencing prognosis with adequate reference to etiology (Tchanturia et al., 2013).

Since receiving an accurate diagnosis, I have not been readmitted since. During my assessment, the psychiatrist said something to me that will stay with me for the rest of my life: “There is nothing wrong with you, you are autistic. You have a different way of experiencing and processing the world, yes. Different; not wrong.”

Small Changes, Big Impact

This meant I needed a different approach to eating disorder recovery. My treatment team created and adhered to a structured plan with consistency in time, place, and support. I had more time to process changes and accommodations were made for my sensory needs. We focused on having an emphasis on enough food and not necessarily on variety. This is an example of a more systematic approach that allows for adaptations to standard treatment methods or goals, which is a treatment need for this population (Kinnaird et al., 2019).

Discovering I am autistic saved my life. Fatal outcomes are influenced by perceived social functioning levels, something that is known to be disrupted for autistic individuals (Zucker et al., 2007). This compounds with the known mortality rates associated with eating disorders both by physiological complications and suicide. It has helped me and those close to me better understand my experience of the world. It has led to small adjustments in my day-to-day life that have improved how I regulate myself and reduce the feeling of being wrong. It is very much a journey and unmasking will take time. Learning who I truly am will take time, as will healing the younger version of myself who was distressed for much of my life with no understanding of why I felt the way I did. However, armed with a greater understanding of autism, I am healing. I am four years out of hospital and six years out of mental health institution admissions. I have recently completed my psychology degree, spoken at international conferences, delivered trainings across the country, and am an autistic champion for the United Kingdom Parliament. I cannot go back and change what I have been through, but I am determined to ensure others do not experience the same. I celebrate being different. As one of my favorite quotes by Dr. Seuss states, “Why fit in when you were born to stand out?” (Easy Bib, 2020).

Hollings, F., Ortiz, M., & Ross-Nash, Z. (2025, November). Influence of autism diagnosis on anorexia nervosa pathology and prognosis. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 61(1)

https://societyforpsychotherapy.org/influence-of-autism-diagnosis-on-anorexia-nervosa-pathology-and-prognosis/

Authors

Fiona Hollings, BS

Fiona graduated wither Bachelor of Science in Psychology in 2025. She has lived experience that directly relates to the information portrayed in this article, as she was diagnosed as autistic at the age of 24, 10 years after her diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. This diagnosis helped Fiona understand herself in a whole different way. She is often found speaking at conferences, sharing insights on podcasts, and spreading awareness relating to the comorbidity that is anorexia nervosa and autism. Fiona uses diagnosis language with reference to her experience, attributing much of her strengths, weaknesses, and characteristics of self to being autistic. Importantly, this diagnosis enabled the reasonable adjustments that have finally helped Fiona start to heal. It is why she so passionately speaks about the importance of being curious about autism, encourages the acceptance of autistic people, and emphasizes the importance of addressing the overlap between autism and eating disorders.

Maria Ortiz, LMHC (she/her) graduated with a Master of Science in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Keiser University. She currently is a co-owner of BreakFree Therapy Services, LLC. Maria provides individual, group, and family psychotherapy specializing in eating disorders for all ages with an emphasis on children and faith-based counseling upon request. As a D1 gymnast, Maria also is equipped to work with athletes as well.

Maria is a leading voice in the eating disorder community, and was a Key Note Speaker at “Normal is Overrated”, a Kids Minds Matter Event.She continues to run in-services and educational trainings for professionals at neighboring community mental health centers and hospital systems given her expertise in eating disorders.

Maria is a published author, with her Coming Back To Myself book and workbook being the first 2 releases in the Finding Freedom series.

Maria received her Bachelor of Science in Human Physiology from University of Iowa which allows her to provide collaborative and informed care needed within the eating disorder field. She is paneled on the National Registry Emergency Medical Technician and has experience working in rehabilitation for a dual diagnosis inpatient/residential facility.

Zoe Ross-Nash, PsyD

Dr. Zoe Ross-Nash (she/her) earned her PsyD in Clinical Psychology at Nova Southeastern University and completed an APA accredited internship at the University of California, Davis in the Eating Disorder Emphasis. Dr. Ross-Nash is currently an assistant professor at Ponce Health Sciences University and a licensed psychologist in private practice. Ross-Nash won the Division 29 Student Excellence in Clinical Practice Award in 2022 and is the Editor for Electronic Communications for the division, after serving three years as the associate editor. Zoe's clinical interests include trauma, eating disorders, wellness, mentorship, and advocacy.

She is originally from Allendale, New Jersey and earned her bachelor's degree in Psychology with a minor in Human Service Studies and Dance from Elon University. In her spare time, Zoe likes to practice yoga and ballet, read and write poetry, and try new restaurants with her loved ones.

References

Brede, J., Babb, C., Jones, C., Elliot, M., Zanker, C., Tchanturia, K., Serpell, L., Fox, J., & Mandy, W. (2020). “For me, the anorexia is just a symptom, and the cause is the autism”: Investigating restrictive eating disorders in autistic women. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 4280–4296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04479-3

Brown, C. M., Hedley, D., Hooley, M., Hayward, S. M., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Krug, I., & Stokes, M. A. (2024). Hiding in plain sight: Eating disorders, autism, and diagnostic overshadowing in women. Autism in Adulthood. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2023.0197

Cage, E., Di Monaco, J., & Newell, V. (2018). Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 473–484.

Crane, L., Batty, R., Adeyinka, H., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., & Hill, E. (2018). Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: Perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3761–3772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1

Easy Bib. (2020, November). Dr. Seuss quotes and facts. https://www.easybib.com/guides/quotes-facts-stats/dr-seuss/

Gregersten, E., Mandy, W., & Serpell, L. (2017). The egosyntonic nature of anorexia: An impediment to recovery in anorexia nervosa treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02273

Hollings, F. (2025). The bubble of anorexia [Infographic]. [Unpublished image].

Kinnaird, E., Norton, C., Stewart, C., & Tchanturia, K. (2019). Same behaviours, different reasons: What do patients with co-occurring anorexia and autism want from treatment? International Review of Psychiatry, 31(4), 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1531831

Maïano, C., Normand, C. L., Salvas, M. C., Moullec, G., & Aime, A. (2016). Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Autism Research, 9(6), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1568

National Autistic Society. (n.d.). Masking. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/masking

Odent, M. (2010). Autism and anorexia nervosa: Two facets of the same disease? Medical Hypotheses, 75(1), 79–81. https://doi.org/j.mehy.2010.01.039

Postorino, V., Kerns, C. M., Vivanti, G., Bradshaw, J., Siracusano, M., & Mazzone, L. (2017). Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(12), 92.

Tchanturia, K., Smith, E., Weineck, F., Fidanboylu, E., Kern, N., Treasure, J., & Cohen, S. B. (2013). Exploring autistic traits in anorexia: A clinical study. Molecular Autism, 4(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-4-44

White, S. W., Oswald, D., Ollendick, T., & Scahill, L. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 216–229.

Zucker, N. L., Losh, M., Bulik, C. M., LaBar, K. S., Piven, J., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2007). Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: Guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes. Psychological Bulletin, 133(6), 976–1006. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.976