Eating Disorder Symptom Presentation Across Different Athletes

This blog is derived from and in reference to the Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy Bulletin.

While eating disorders are prevalent across all communities, eating disorders in athletes have an even higher occurrence rate than the general population. Approximately 19% of athletes endorse eating disorder pathology, while it occurs in about 9% of the general population (Ghazzawi, et al., 2024; Pike, 2024). Some research indicates these numbers are even higher, with 19% of male athletes and 45% of female athletes struggling with disordered eating (The Emily Program, 2023). Considering symptomology globally, Eastern countries had higher rates when compared to Western countries. Additionally, indoor sports were more likely to engage in eating disorder behaviors like restriction, binge eating, and purging, while outdoor sports were less likely (Ghazzawi, et al., 2024).

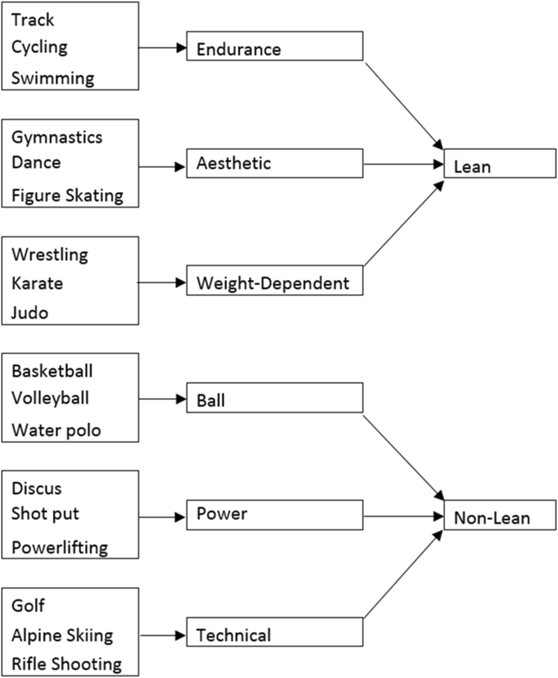

It has been observed that sports that require a designated weight class or aesthetic, like gymnastics or wrestling, are at a higher risk for eating disorders. Sports can be broken down into a two-prong system of “lean” and “non lean” athletes. Figure 1, as cited in Mancine and colleagues (2020), expertly describes how sports are categorized in this dichotomy.

Around 42% of athletes in athletics sports, 24% in endurance sports, 17% in technical sports, and 15% in ball game sports endorsed disordered eating pathology. These athletes also are eight times more likely to be injured as well. (The Emily Program, 2023). The term Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) has been coined to demonstrate the negative physical consequences that occur to the body specifically for athletes given the frequency of this occurring in these communities. Sadly, and unsurprisingly, disordered eating behaviors also increase the likelihood of injury and poor performance outcomes (Melin, 2014). Due to the diverse catalysts and reasons for maintenance of pathology, symptoms presentation of disordered eating across different sports may vary.

Aesthetic Sports

Dancers

Dance requires high levels of perfectionism (Penniment & Egan, 2012), given the level of dedication required to obtain mastery over the technique. Dance schools also have a history of toxic environments, with social comparison as a driving force of negative self-evaluation (Rasheed & Runswick, 2024). Strict teaching methods, favoritism, competition for parts lend to dancers “doing what it takes” to achieve the ideal body type, which is thin, lean, and slender. Unsurprisingly, dancers have a higher risk of struggling with disordered eating, specifically, they are three times more likely to experience an eating disorder. While other specified feeding of eating disorders occurred in 14.9% of one study sample, it is unsurprising that anorexia and bulimia occurred in around 4% of the community (Arcelus, et al., 2014). Around 83% of dancers endorse a history of eating disorder pathology in their lifetime (Ringham et. al, 2006). Some studies have indicated that even when not satisfying the full criteria for a diagnosis of an eating disorder, dancers experience the same severity of body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness at comparable rates to folks who have a clinically significant eating disorder (Stice, 2002).

Equestrian

It has been documented that participation in appearance-based sports can increase the likelihood of disordered eating dude to the pressure to be thin. Consequently, athletes may begin to engage in behaviors like restriction (Torres-McGehee, 2011). Equestrian athletes are typically not the first that come to mind for clinicians when it comes to an aesthetic sport, however in both English and Western riders, the frequency rates of eating disorders were just as high as other appearance-based sports. Additionally, they were more likely to label their body as significantly larger than their actual size, driving a desire for a smaller body in both their normal clothing and competitive uniforms (Torres-McGehee, 2011). An article featured on Equus Magazine, a self-proclaimed “horse owner’s resource”, shared the adage “losing weight and riding better” (Ellis-Ashburn, 2017), while another mentioned that being “flat chested” is the ideal body type for a rider (Equiculture, 2021). Some websites claim that the extra weight of the rider is detrimental to the horse. As such, it has been studied that body dissatisfaction and social comparison related to physique were elevated in this community (Monsma, 2013).

Figure Skating

Around 13% of female skaters reported scores indicative of disordered eating. Additionally, prevalence did not change when accounting for elite or sub-elite female skaters (Voelker et. al., 2014). However, one study detailed that when assessed, 36% of skaters were currently dieting and 11% endorsed binge eating behavior. When considering gender, around 40% of male skaters reported being terrified about gaining weight, within female skaters, that number was nearly doubled (Jonnalagadda et al., 2004). The drive for thinness is not just internal, outside pressures occur from coaches and society. Wilmore (1991) found that 55% of female athletes have felt the pressure to lose weight or maintain a certain weight. Some folks in the skating community use safety as a precaution to stay thin, noted that when a skater lands a jump, the athlete absorbs around eight times their body weight (Liszewski. 2014). One athlete describes her own experience of people sharing she would “jump higher” during eras of her life where she was thinner, where she was “sluggish” in the moments she was heavier (Chinault, 2019).

Gymnastics

Gymnastics requires long training hours, compliance and submission to coaches, and perfectionism: a terrifying trio. This becomes a worrisome dynamic when it comes to food and body. Success in gymnastics judges athletes based on their body shape, the line the side of the body makes visually, and prioritizes that body parts like stomachs and glutes are “tucked in.” With this in mind, it is no surprise that one study showed that over three fourths of gymnasts exhibit weight dissatisfaction, stating they believe they are bigger than what would be ideal for their body (Francisco et al., 2012). There is also a strong correlation between the competitive level within the sport and eating disorder behaviors, as higher-level elite athletes exhibited higher scores on eating disorder assessment tools than their non-competitive peers (Kontele et al., 2022). It is imperative to address the culture of the sport, with sayings contributing to the onset of eating disorders, including “thin to win” and “be lighter; fly higher.” Gymnasts can often practice upwards of 36 hours a week from a young age, hearing these comments and pressures consistently during formative years. Due to how common disordered eating as a whole is within the sport, one study labeled the requirements of eating disorders as “problematic” due to its inability to adequately transfer into such a high demand setting and standard (Tan et al., 2016). This is further confirmed by another study’s findings that high level sports of this nature tend to normalize maladaptive eating behavior and rigidity around body shape and size, while the medical setting would pathologize these symptoms (Bloodworth et al., 2015).

Endurance

Swimming

There is an immense pressure placed on swimmers to achieve a lower body weight due to a common misconception that it improves swim times (Melin, 2014). Some studies have suggested the high prevalence of disordered eating in swimming is due to the type of swimsuits required in competition (Benson et al., 1990). There is also evidence that in sports with revealing attire, it more easily facilitates body checking and social comparison (Reel & Gill, 2011; Steinfeldt et al., 2013). Artistic swimming combines dance, swimming, and gymnastics, perpetuating eating disorder pathology of both endurance and aesthetic sport. The precise synchronization and homogeneity of bodies contributes to the overall performance result (Parlov, 2020), thus increasing desire for thinness to not stand out. However, in one study, swimmers reported higher rates of body satisfaction due to the tendency to have a body more aligned with the thin ideal. Yet, this satisfaction plummeted when assessed while the athletes were swimming, likely due to the strict demands of their sport (Assyifa & Riyadi, 2023).

Track

Track is a sport that comes down to fractions of a second to win. This creates not just a physical challenge to be the best, but also a mental challenge to remain focused on technique and timing that must be incredibly precise. Unlike some other sports, an example of gymnastics mentioned above, some studies have not shown a strong correlation between division or level of sport and the correlation to eating disorder pathology (Quinn & Robinson, 2020). The Latvian Academy of Sport Education found that the primary apprehension within this population was body shape (Gabarajeva & Vazne, 2017). Track is unfortunately a sport that has a societal stereotype relating to body size and shape, creating a unique pressure within the sport to “look” like a track athlete (Quinn & Robinson, 2020). Another study solidified this stereotype by finding that there is often an actual emphasis on being lean over focus on the actual physical demands of training (Hulley & Hill, 2001). There does seem to be a dissimilarity between male and female track athletes, with female competitors reporting correlations between their eating patterns and performance and weight and emotions more consistently than their male counterparts (Krebs et al., 2019).

Weight Dependent

Wrestling

Cutting weight is a commonly accepted practice in the wrestling community. Cutting weight is the term used when athletes will engage in extreme behaviors to be able to compete in a weight category that varies from their typical weight. Once the season is over, the weight is usually gained back rapidly (Shriver et al., 2009). Motivation to cut weight varies, according to the Perriello (2001) some athletes wrestle at a lower weight class to avoid a better wrestler who is at their natural weight, or to aid their team in filling a weight class spot. Along with calorie restriction, there are additional behaviors associated with cutting weight in wrestlers than what is typically seen with aesthetic sport. Running/jogging (73%), exercise using a device (bike, jump rope; 59%), rubber suit/nylon top (34%, and sauna (14%) were most common behaviors. Vomiting and diuretics only occurred in 8% and 2% of wrestlers, respectively (Perriello, 2001; Rea, 2013). Assessment around gradual and acute cutting is important with this community (Rea, 2013).

Ball

Volleyball

Though society would not quickly associate volleyball with eating disorders, this sport is not immune to this pathology. One study found that 50% of the participants were in line with being at risk for disordered eating, with these athletes reporting one or more episodes of bingeing per month, as well as restricting their oral intake; one competitor also reported vomiting (Vargas et al., 2013). This is a sport where clothing is short and tight, allowing for increased body comparisons as well as pressure to fit in the uniform. One study found that 60% of athletes reported they feel there is “aesthetic judgement” within the sport (Fochesato et al., 2021). This is exacerbated by media pressures, as illustrated in a World Nutrition study, showing a strong negative correlation between media exposure/comparison and body image satisfaction (Türkmaya Şanal et al., 2022). Volleyball is also another example of a sport where division or level of competition influenced risk of eating disorder development (Beals, 2002). Though considered non-aesthetic, assessment for pressures relating to aesthetic appearance cannot be ignored in this population of athletes.

Power

Body Building

Body Building, a sport with a strong emphasis on visual physique, has a strong culture that normalizes eating disorder symptoms and presentation. This sport showed an increase in the presence of bulimic behaviors and overall dissatisfaction with appearance in men, even when compared to other male athletes (Goldfield et al., 2006). There is an extreme lack of research and resources relating to the impact and prevalence of eating disorders specifically in the female body building community, though special attention has been given to the responsibility and accountability of training professionals and coaches in this industry (Money-Taylor et al., 2021). Body Building also emphasizes the utility and function of food, rather than enjoyment or satisfaction, with 74% of participants in one study reporting that they eat based off their recommended schedule requirements rather than off their level of hunger or desire for food (Mangweth et al., 2001). Though physique is a priority, there is special attention given to fat percentage within the body, resulting in significant levels of discrepancy reported between actual versus perceived ideal fat percentage in male body builders (Devrim et al., 2018). More attention needs to be given to eating disorder symptom presentation for women within this sport, as shown by glaring differences in available research.

Technical

Golf

This sport of technicality, precision, and repetition, sees a prevalence rate of eating disorders between 11 and 17% (Torres-McGehee et al., 2011; Miracle, 2013). There is extremely limited accessibility to resources relating to eating disorder prevalence and prognosis associated with these athletes. Golf is a “non-lean” sport, meaning body weight and shape is not associated with success, achievement, or progress (Mancine et al., 2020). Golfers are under an immense amount of pressure to be perfect, with their mastery of their craft being assessed 18 times within a single game, making the frequency of evaluation of overall sport performance incredibly high (Fleming & Dorsch, 2024). Not only do they have the similar experience to other athletes of comparing themselves to others in the match, but they also have the unique experience of comparing themselves to the set “par,” which increases the impact of judgement relating to failure versus success significantly (Fleming & Dorsch, 2024). Perceived failure within athletes can absolutely be considered a risk factor associated with the origination of an eating disorder. Assessing for perception of success vs failure is paramount with this community, as well as any associated punishments, rewards, or superstitions/rituals.

What Coaches Can Do

Education

Coaches should do their own research, attend continuing educations on eating disorders such as conferences and presentations, and keep up with new literature about these disorders. It is imperative that coaches learn the warning signs and symptoms of an eating disorder to be able to spot them if they come across their track, studio, mat, or field. Not only is it important to know the general or common symptom presentation for disordered eating or eating disorders, but it is also more important for coaches to know what this presentation looks like within the specific sport itself. Studies have shown that coaches are lacking in education and understanding of eating disorder presentation within athletes, including how risk factors present, nature of the disorder, treatment protocols, or prevention efforts (Turk et al.,1999). Coaches need to be educated on what to look for, then what to do.

Awareness

Know the prevalence within your sport. Studies illustrate that most coaches will report that they do not believe that their sport has a strong association with eating disorders, even if they have personally coached athletes with a known eating disorder diagnosis (Nowicka et al., 2013). Coaches can be a frontline individual to notice and ask athletes if they could use any support relating to food and body. Coaches often see their athletes for multiple hours in a day, giving them access to information about individuals and their behavior that even family members or friends may not have. This is where the importance of education comes in, as coaches must know when to ask and how. One study found that most coaches would score between 70 and 79.5% on an assessment relating to multiple aspects within the scope of eating disorders; Almost 10% of coaches even scored below 60% (Turk et al.,1999). For disorders with the highest mortality rate among mental health disorders, these percentages could lead to catastrophic outcomes. Coaches should be screening their athletes for healthy eating habits and appropriate amounts of exercise and use language that strengthens the idea that food is fuel and is crucial to the long-term success in life and in sport. The Eating Disorder Screen for Athletes assessment found here can be a great resource.

Action

Coaches need to be aware of their local resources and referral options. Many coaches, specifically in college athletics environments, may be aware of their specific services offered within the school. However, it is imperative that individuals with eating disorders receive specialized care, not just generalized psychological or nutritional support. Coaches should reach out to local agencies or national organizations for eating disorders if they need help or guidance with how to move forward. Early intervention is key for improving prognosis. Quick, efficient, and adequate steps to help an athlete receive help is so vital to their long-term health and well-being. Coaches also need to play a crucial role on a treatment team, and their involvement is essential for adequate treatment. Coaches can follow their own philosophy, that athletes need help and guidance for success on the mat. They might just need the same amount of help off it too.

Co-Authors

Maria Ortiz, LMHC, CEDS

Maria Ortiz, LMHC, CEDS graduated with a Master of Science in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Keiser University. She currently is a co-owner of BreakFree Therapy Services, LLC. Maria provides individual, group, and family psychotherapy specializing in eating disorders for all ages with an emphasis on children and faith-based counseling upon request. As a D1 gymnast, Maria also is equipped to work with athletes as well. Maria is a leading voice in the eating disorder community, and was a Key Note Speaker at “Normal is Overrated”, a Kids Minds Matter Event. She continues to run in-services and educational trainings for professionals at neighboring community mental health centers and hospital systems given her expertise in eating disorders. Previously she authored, edited, and managed a monthly eating disorder blog disseminating pertinent information to her community. Maria received her Bachelor of Science in Human Physiology from University of Iowa which allows her to provide collaborative and informed care needed within the eating disorder field. She is paneled on the National Registry Emergency Medical Technician and has experience working in rehabilitation for a dual diagnosis inpatient/residential facility.

Dr. Zoe Ross-Nash (she/her) earned her PsyD in Clinical Psychology at Nova Southeastern University and completed an APA accredited internship at the University of California, Davis in the Eating Disorder Emphasis. Dr. Ross-Nash is currently an assistant professor at Ponce Health Sciences University and a licensed psychologist in private practice. Ross-Nash won the Division 29 Student Excellence in Clinical Practice Award in 2022 and is the Editor for Electronic Communications for the division, after serving three years as the associate editor. Zoe's clinical interests include trauma, eating disorders, wellness, mentorship, and advocacy. She is originally from Allendale, New Jersey and earned her bachelor's degree in Psychology with a minor in Human Service Studies and Dance from Elon University. In her spare time, Zoe likes to practice yoga and ballet, read and write poetry, and try new restaurants with her loved ones.

References

Arcelus, J., Witcomb, G. L., & Mitchell, A. (2014). Prevalence of eating disorders amongst dancers: a systemic review and meta‐analysis. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(2), 92-101.

Assyifa, R., & Riyadi, H. (2023). Correlation between body image, eating disorders, and nutrient adequacy level with nutritional status of adolescent swimmers in Bogor City, Indonesia: Hubungan Persepsi Tubuh, Gangguan Makan, dan Tingkat Kecukupan Gizi dengan Status Gizi Atlet Renang Remaja di Kota Bogor, Indonesia. Amerta Nutrition, 7(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.20473/amnt.v7i1.2023.98-111

Beals, K. A. (2002). Eating behaviors, nutritional status, and menstrual function in elite female adolescent volleyball players. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(9), 1293–1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90285-3

Benson, J. E., Allemann, Y., Theintz, G. E., Howald, H. (1990). Eating problems and calorie intake levels in Swiss adolescent athletes. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 11 (4), 249-252.

Bloodworth, A., McNamee, M., & Tan, J. (2015). Autonomy, eating disorders and elite gymnastics: Ethical and conceptual issues. Sport, Education and Society, 22(8), 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1107829

Burton, I. (2021). A Critical Review of Eating Disorders in Female Athletes and Evidence-Based Interventions for Sports Coaches. https://doi.org/10.31236/osf.io/g2kqw

Chinault, E. M. (2019). My experiences with body image and eating disorders in figure skating. Publication No. 2572-4339. [Undergraduate Thesis, University of Soth Florida St. Petersburg]. Digital Commons https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/honorstheses/248

Devrim, A., Bilgic, P., & Hongu, N. (2018). Is there any relationship between body image perception, eating disorders, and muscle dysmorphic disorders in male bodybuilders? American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(5), 1746–1758. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318786868

Ellis-Ashburn, H. (2017) Losing weight and riding better. Equus. Retrieved at: https://googleads.g.doubleclick.net/pcs/click?xai=AKAOjsv4emPAspAKqEmqW5tAL8AI9F47kHhWY-C8q6BiTqa6Kk6MeYPAWytGXxdKehUPSNI1xJRrAWVpVVRF7JAKQusSlXZdOeC_fPnK6vtEAArwETcMLfAuCRliqJac_vys3PTO_ul-5eh5L0SqmEeTQc01ZdI68oN2rHKzwY25fQUyNNf4aSPJNCLFw0iIRNsw90BREv5S3pAXs0BRqkR0ekrrbZP8ad2pcY70Kvvcj8QdCJYRsvDbcO-WDA0joN4FeJzDsaxinLVKIXKxGx6KQF37gylZMFpLC22TtfEpDeMXy-jIqgZpv4CpUYfk-qpGQUubCe0CGisVAcQwl4H0KmFx&sai=AMfl-YTbONP3eA7jGnxns8coRmzylvRBzdSQxM2Rvbu6vNYc9g89eZkY1g05OkSJsEjQaF-iE-3N4dNqfeUDPdjMzn4rDOrVJ6BXE7SWDZbDy-efcq9Pu3gQGi9NuJqp&sig=Cg0ArKJSzO8R3nVivybV&fbs_aeid=%5Bgw_fbsaeid%5D&adurl=https://mynewhorse.equusmagazine.com/2024/08/30/one-year-anniversary-giveaway/&nm=4&nx=285&ny=-341&mb=1

Fleming, D. J., & Dorsch, T. E. (2024). “there’s no good, it’s just satisfactory”: Perfectionism, performance, and perfectionistic reactivity in NCAA student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2024.2410282

Fochesato, R., Guidotti, S., & Pruneti, C. (2021). Risk of developing eating disorders through the misperception of the body image and the adoption of bad eating habits in a sample of young volleyball athletes. Archives of Food and Nutritional Science, 5(1), 007–017. https://doi.org/10.29328/journal.afns.1001027

Francisco, R., Alarcão, M., & Narciso, I. (2012). Aesthetic sports as high-risk contexts for eating disorders — young elite dancers and gymnasts perspectives. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n1.37333

Gabarajeva, L., & Vazne, Ž. (2017). Eating Disorders And Disordered Eating Behaviors In Female Track and Field Athletes. LASE Journal of Sport Science, 8(2), 3–13.

Ghazzawi, H.A., Nimer, L.S., Haddad, A.J., Alhaj, O.A., Amawi. A.T., Pandi-Perumal, S.R., Trabelsi, K., Seeman, M. V., Jahrami, H. (2024). A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of the prevalence of self-reported disordered eating and associated factors among athletes worldwide. Journal of Eating Disorders 12(24). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-024-00982-5

Goldfield, G. S., Blouin, A. G., & Woodside, D. B. (2006). Body image, binge eating, and bulimia nervosa in male bodybuilders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51(3), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370605100306

How can you ride well when you do not have a perfect body (2021). Equiculture. Retrieved at: https://www.equiculture.net/blog/your-body-and-how-it-affects-your-riding#:~:text=The%20’ideal’%20shape%20is%20relatively,rider%20and%20raises%20their%20CoG).

Hulley, A. J., & Hill, A. J. (2001). Eating disorders and health in Elite Women Distance Runners. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30(3), 312–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1090

Jonnalagadda, S. S., Ziegler, P. J., & Nelson, J. A. (2004). Food preferences, dieting behaviors, and body image perceptions of elite figure skaters. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 14(5), 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.14.5.594

Kontele, I., Vassilakou, T., & Donti, O. (2022). Weight pressures and eating disorder symptoms among adolescent female gymnasts of different performance levels in Greece. Children, 9(2), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020254

Krebs, P. A., Dennison, C. R., Kellar, L., & Lucas, J. (2019). Gender differences in eating disorder risk among NCAA Division I Cross Country and track student-athletes. Journal of Sports Medicine, 2019, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5035871

Liszewski, A. (2014). Sensors show figure skaters absorb 8x their own body weight after jumps. Gizmodo. Retrieved at: https://gizmodo.com/sensors-show-figure-skaters-absorb-8x-their-own-body-we-1526842854

Mancine, R.P., Gusfa, D.W., Moshrefi, A. & Kennedy S. F. (202) Prevalence of disordered eating in athletes categorized by emphasis on leanness and activity type – a systematic review. Journal of Eating Disorders 8(47). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00323-2

Mangweth, B., Hausmann, A., Pope, Jr., H. G., & Kemmler, G. (2001). Body Image and Psychopathology in Male Body Builders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics.

Melin, A., Torstveit, M. K., Burke, L., Marks, S., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2014). Disordered eating and eating disorders in aquatic sports. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 24(4), 450-459.

Miracle, A. (2013). Evaluation of the Relationship between Nutrition Knowledge and Disordered Eating Risk in Female Collegiate Athletes . UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones.

Money-Taylor, E., Dobbin, N., Gregg, R., Matthews, J. J., & Esen, O. (2021). Differences in attitudes, behaviours and beliefs towards eating between female bodybuilding athletes and non-athletes, and the implications for eating disorders and disordered eating. Sport Sciences for Health, 18(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-021-00775-2

Monsma, E. V., Gay, J. L., & Torres-McGehee, T. M. (2013). Physique Related Perceptions and Biological Correlates of Eating Disorder Risk among Female Collegiate Equestrians. J Athl Enhancement 2: 2. of, 8, 2. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2324-9080.1000107

Nowicka, P., Eli, K., Ng, J., Apitzsch, E., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2013). Moving from knowledge to action: A qualitative study of Elite Coaches’ capacity for early intervention in cases of eating disorders. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 8(2), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.8.2.343

Parlov, J., Low, A., Lovric, M., & Kern, R. (2020). Body mass index, body image dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms in female aquatic sports: Comparison between artistic swimmers and female water polo players. Journal of physical education and sport, 20, 2159-2166.

Penniment, K.I. & Egan, S.J. (2012). Perfectionism and learning experiences in dance class as risk factors for eating disorders in dancers. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, 13-23.

Perriello, V. (2001). Aiming for healthy weight in wrestlers and other athletes. Contemporary Pediatrics 18 (9), 55-74.

Pike, E. (2024). Eating disorder statistics 2024. Eating Recovery Center. Retrieved from: https://www.eatingrecoverycenter.com/resources/eating-disorder-statistics#eating-disorder-statistics

Quinn, M. A., & Robinson, S. (2020). College athletes under pressure: Eating disorders among female track and field athletes. The American Economist, 65(2), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0569434520938709

Rea, J. (2013). Weight Loss Methods and Eating Disorder Risk Factors in Collegiate Wrestlers. Publication No. 1545775. [Master’s Thesis, Indiana State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Rasheed, E., & Runswick, O. R. (2024). “It Was All Very Toxic”: An Initial Exploration into Dancers’ Experiences of Social Comparison in UK Dance Schools. Journal of Dance Education, 1-12.

Reel, J.J. & Gill, D.L. (2001). Slim enough to swim? Weight pressures for competitive swimmers and coaching implications. Sport Journal, 4(1), 5.

Ringham, R., Klump, K., Kaye, W., Stone, D., Libman, S., Stowe, S., et al. (2006). Eating disorder symptomatology among ballet dancers. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(6), 503- 508.

Steinfelt, J.A., Zakraisek, R. A., Bodey, K. J., Middendorf, K. G., Martin, S. B. (2013) Role of uniforms in the body image of female college volleyball players. Counseling Psychologist, 41, 791-819.

Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 128(5), 825–848.

Tan, J. O., Calitri, R., Bloodworth, A., & McNamee, M. J. (2016). Understanding eating disorders in elite gymnastics. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 35(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2015.10.002

Torres-McGehee, T. M., Monsma, E. V., Gay, J. L., Minton, D. M., & Mady-Foster, A. N. (2011). Prevalence of eating disorder risk and body image distortion among National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I varsity equestrian athletes. Journal of athletic training, 46(4), 431-437.

Turk, J., Prentice, W., Chappell, S., & Shields, Jr., E. (1999). Collegiate Coaches’ Knowledge of Eating Disorders. Journal of Athletic Training.

Türkmaya Şanal, S., Türker, P. F., Köse, B., & Yeşil, E. (2022). The relationship between media image, body image, and nutritional status: Research on professional female volleyball players. World Nutrition, 13(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.26596/wn.202213176-87

The impact of eating disorders on athletic performance (2023). The Emily Program. Retrieved at: https://emilyprogram.com/blog/the-impact-of-eating-disorders-on-athletic-performance/#:~:text=Sports%20emphasizing%20designated%20weight%20classes,an%20athlete%20can%20be%20difficult.

Vargas, S. L., Kerr-Pritchett, K., Papadopoulous, C., & Bennett, V. (2013). Dietary habits, menstrual health, body composition, and eating disorder risk among collegiate volleyball players: A descriptive study. International Journal of Exercise Science, 6(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.70252/abhl8758

Voelker, D. K., Gould, D., & Reel, J. J. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of disordered eating in female figure skaters. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15(6), 696-701. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.12.002

Wilmore, J. (1991). Eating and weight disorders in the female athlete. International Jounral of Sport Nutrition, 1(2), 104-117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsn.1.2.104